Why the Fed Can’t Save US Now

Too Little, Too Late. A Difficult Year Lies Ahead

Overview

The Federal Reserve (the Fed) plays a critical role determining near-term interest rates. Its policy directive is to maintain stable inflation and low unemployment. This directive is called the “Dual Mandate”.

Business cycles are often formed by fluctuations in economy-wide demand conditions. Too much demand leads to inflation. Too little demand leads to unemployment. By the raising or lowering the Federal Funds interest rates, among other monetary tools, the Fed can inject or reduce demand in the overall economy.

This “countercyclical demand management” policy is not precise. Raising rates too fast could result in recession. Lowering them to quickly could result in inflation. As such, it is prudent for the Fed to take small steps to avoid over correcting. In addition, the policy actions do not produce immediate results making the calibration of policy even more difficult.

Finally, the direction of monetary policy is clear when its either elevated inflation or high employment. Fed policy can address one – not both. Unfortunately, today’s economy is characterized by both increases in inflation and unemployment. The last time it happened was in the 1970s. This creates a problem for the Fed. What does it fight: Inflation? Unemployment?

Current Policy: Sit

The Fed last policy action was late December 2024. At that point, inflation was gradually easing and signs that the economy was cooling were beginning to emerge. Since then, progress in reducing inflation to the Fed’s target rate of 2% has not materialized as expected. While signs that an economic slowdown have been melting, labor markets have been strong enough. Lacking a clear direction of the economy’s path, the Fed sat – neither raising or lowering rates.

Tariffs raise the prospect of higher inflation. Tariffs simultaneously threaten near term economic growth and labor market strength. It will take time for these forces to develop and be clearly seen in the data. For now, this suggests the Fed will continue to sit. The slow emergence in data and the uncertainty regarding policy directive could make the sit a bit longer than some expected.

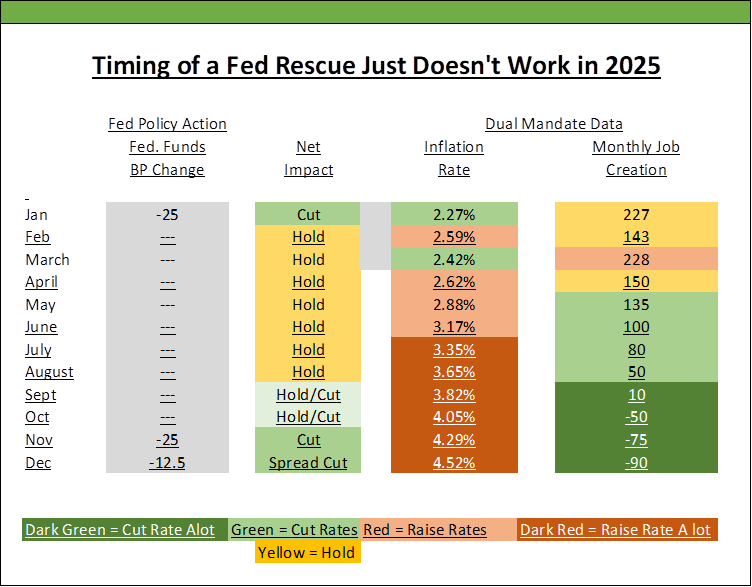

A recent survey of Federal Reserve Governors on policy actions for 2025 showed 9 Governor in favor of two 25 BP cuts, 8 in favor of one or no cuts, and 2 in favor of more aggressive cuts. There is no clear consensus on near term policy direction. Moreover, the threats facing Fed policy is not either fighting inflation of unemployment – it’s both. Between the two evils, most Federal Reserve Governors consider inflation the more potent threat to the economy and lean toward fighting that as its prime directive.

When the Fed Will Act

The potential slowdown in economic growth, by itself will bring down inflation. By delaying the timing of a next move, and allowing recessionary spirits to brew a bit longer than, inflation may ease to levels that the Fed is comfortable with. Following this logic, the next move will be to cut.

A lot of time has to pass for all that to happen. According to this scenario, even as momentum of the recession/downturn gains strength, the Fed will sit. Only after the threat of higher unemployment reaches a level to ensure an easing in inflation, will the Fed act to cut. Because of uncertainty of results regarding monetary policy actions, the initial steps are expected to be modest – 25 BP at a time. Any action to cut rates will not materialize until the second half of 2025 – if then.

As soon as the Fed makes a cut, don’t expect immediate results. While there will be some immediate results that materialize in some sectors, such as finance, the full impacts of a rate cut on the economy take a long time. The effect of a rate cut policy gradually builds, reaching a maximum impact, and then the effect of the cut gradually fades. Economists estimate the lag as long as 18 months.

At that point, the cow is out of the barn (I am never sure what animal escaped but I know it’s a bad thing). Adverse economic momentum, once in place, is hard to reverse. Initial steps by the Federal Reserve will be viewed as a policy of too little, too late to save a recovery for the US economy.

Delays in policy actions, Long wait for full impact, too late to help 2025

Economic growth could turn negative. Some may refer to it as a recession. But in the context of rising inflation, this suggests a form of “stagflation” whereby the economy experiences the concurrent malady of rising unemployment and inflation the meantime, the economy is expected to drift weaker – giving rise to more aggressive rate cuts.

In the meantime, interest rates will only slowly drift lower as demand in the overall economy eases. For the most part, key interest rates, such as 30-year conventional mortgage rates will remain near the 6.5% to 7% range through the first half of 2025 – and well into the second half. These high rates will be set in context of a weakening labor market. By the third quarter monthly job creation could near zero – from an average of 150,000 net new jobs currently.

Timing is everything. Take construction related industries. The 80% of all construction activity is typically completed by the end of the third quarter. The Fed might only be starting its rate cuts at that time. Then take into account the policy lag issue. And this the context in which business will try to salvage a year of growth.

It’s not going to happen. Too little. Too Late. The Fed won’t save us this year. A difficult year lays ahead. The odds of recession are high.

Subscribe to The Sullivan Report. The Sullivan Report is a regular (weekly) report that looks at key forces working in the economy and provides insight hoping that business and individuals can make better respond decisions.

Brief Bio

Ed Sullivan has held senior level positions at the Portland Cement Association, Chase Manhattan Bank Economics, Standard & Poor’s, and Wharton Economics. Ed has lectured at The War College, Fordham University, Fairfield University, Manhattanville College, Villanova and St. Joseph’s University. The Chicago Federal Reserve has cited Ed for his forecast accuracy. While at the CIA, Ed has played supportive analytical roles in major US trade policy including Japan's Voluntary Automotive Export Restraints and NAFTA.